Figure 1. Collaborative Leadership Skills Model for Actionable Change

|

Leadership Characteristics of Extension Agents Facilitating a Healthy Communities, Civic-Engagement Randomized Trial in Rural Towns

Meredith L. Graham1, Galen D. Eldridge1, Margaret Demment1, Meghan Kershaw1, Angel Christou1, Vi Luong1, Elena Andreyeva2, Sara C. Folta3, Karla L. Hanson4, Jay E. Maddock2, and Rebecca A. Seguin-Fowler1

1 Institute for Advancing Health Through Agriculture, Texas A&M University, U.S.A.

2School of Public Health, Texas A&M University, U.S.A.

3Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy, Tufts University, U.S.A.

4Department of Public and Ecosystem Health, Cornell University, U.S.A.

Abstract

Leadership styles and skills are associated with group dynamics, creativity, and project implementation in community change initiatives; specifically, collaborative leadership skills can lead to a greater likelihood of effective, sustainable improvement in the health of communities. This study sought to examine the leadership styles and skills of Extension Agents engaged in leading a community policy, system, and environmental change initiative. Our aim was to describe how collaborative the leadership style of these leaders was and how high they scored in collaborative leadership skills. Data were collected among Extension Agents at baseline (n=7), prior to program training or implementation, focused on leadership style and collaborative leadership skills. A 16-item leadership styles survey was used to assess Agents’ scores for four leadership styles: 1) authoritative; 2) democratic; 3) facilitative; 4) situational. Collaborative leadership skills were measured using the Turning Point Collaborative Leadership Questionnaire, which evaluates key behaviors within the six skills of effective collaborative leaders: assessing the environment, creating clarity, building trust, sharing power and influence, developing people, and self-reflection. Agents were most often authoritative in their leadership style, although four out of seven Agents had two styles tied for highest score. Most Agents scored as excellent in assessing the environment (n=4), sharing power and influence (n=5), and developing people (n=5). The highest proportions were in the strong category for creating clarity (n=4), building trust (n=4), and self-reflection (n=4). While Agents demonstrated variety across the characteristics, there were consistencies both in leadership type and collaborative skills. Clinical Trial #: NCT05002660. ClinicalTrials.gov. Registered 4 August 2021.

Keywords: leadership

style, leadership skills, collaborative, civic engagement, Extension

Nearly 60% of the U.S. adult population suffers from at least one chronic illness such as cancer, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease, which are leading causes of death and disability in the U.S. and key drivers of national annual healthcare costs (Hoffman, 2022). Chronic diseases are largely preventable through improvement of key modifiable risk behaviors such as diet, physical activity (PA), smoking, sleep, and timely health screenings (Willett, 2006). However, structural and environmental factors must also be considered to increase the effectiveness, health equity, and sustainability of chronic disease interventions (Seguin-Fowler et al., 2024). To address such factors, the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Association of County and City Health Officials all recommend policy, systems, and environment (PSE) interventions to support people to lead healthier lives in different environments (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; National Association of County and City Health Officials, September 2018; World Health Organization, 2003). Rural built environments often present unique challenges to these types of interventions, including active transport challenges (e.g., poor pedestrian infrastructure, high speed limits, lack of bike lanes) and long distances to healthy food and PA resources (Hansen et al., 2015). Thus, opportunities to intervene with and evaluate multilevel interventions (i.e., interventions addressing factors beyond the individual level) that promote healthy eating and active living in rural communities are essential.

Rural communities boast a powerful asset: their tightly woven social networks. These networks present a unique opportunity for mobilizing collective action to catalyze PSE change. We refer to this participatory, community-led approach as civic engagement for built environment change (CEBEC) (Seguin et al., 2018). CEBEC leverages civic engagement, which is defined as “individual and collective actions designed to identify and address issues of public concern,” (American Psychological Association) and utilizes the socioecological model to promote health behavior change at each level (i.e., individual, social/collective, community/environment/policy) (McLeroy et al., 1988). Studies, including our own, show that both rural and urban CEBEC initiatives can lead to meaningful built environment and policy changes (e.g., allocation of government funds for built environment improvements, sidewalk repair programs, addition of shade trees to encourage walking, installation of pedestrian flashing light signals) (Adams et al., 2014; Barnidge et al., 2015; Gavin et al., 2015; Hinckson et al., 2017; Schwarte et al., 2010; Sheats et al., 2017). Through this collaborative approach, individuals and local organizations can forge strong partnerships to foster the development of highly relevant, feasible, and sustainable solutions that drive positive community change (Barnidge et al., 2015; Hinckson et al., 2017; Schwarte et al., 2010).

A mainstay of health promotion programs in rural communities, among other areas of service and expertise, is the Cooperative Extension Service, an educational network that provides non-formal, research-based education to counties throughout the nation (United States Department of Agriculture). Extension has offices in or near most of the nation’s ~3000 counties and often has a Family and Consumer Science Extension Agent that leads health promotion programs. County-based Extension Agents (referred to henceforth as Agents) offer research-based classes, workshops, and programs to residents of their counties, including one-time, time-limited, or ongoing health promotion programs. Optimizing the effectiveness of this nationwide set of community health workers holds tremendous potential to improve public health. Understanding Extension Agents’ leadership styles and skills could improve coalition functioning. While there is no superior form of leadership style, knowing one’s style can help identify strengths and minimize weaknesses in leadership (Rubin, 2013). The ability to change leadership styles based on the situation by having multiple styles is also seen as a strength (Sethuraman & Suresh, 2014). This study also provides a baseline assessment of leadership styles that can assess whether their current approaches are appropriate or if adjustments are needed to optimize their impact.

The Change Club (CC) is a CEBEC intervention approach designed to empower community members to assess and improve their built environments by engaging in social action and collective efficacy activities. The CC is led by trained program Agents, who engage a small group of community members that assess the PA and dietary environment to develop an action plan intended to catalyze change in their towns. CC members (CCM) make improvements related to food (for example, offering healthier foods in restaurants or schools) or PA opportunities (for example, parks or walking trails) by following a structured process directed by the program educator (Agent). The CC intervention aims to impact the diet and PA behaviors of CCM, their friends and family, and other community residents who will benefit positively from the built environment and policy changes.

The success of civic engagement initiatives, such as CC, may be influenced by the leadership styles and skills of their group leaders. These factors can directly impact group dynamics, creativity, and project implementation (University of Kansas Center for Community Health and Development). Notably, collaborative leadership skills may foster a higher likelihood of achieving effective, sustainable improvement in the health of communities (Berkowitz, 2000). Leaders facilitate group dynamics, influencing group members’ behavior and behavior change. A variety of leadership styles exist; different leadership styles can be more or less effective depending on the intended outcome. One of the earliest attempts to define leadership styles using research methods was a study published by Lewin, Lippitt, and White in 1939, in which they identified the reactions of boys doing arts and crafts projects under different leadership styles (Lewin, 1939). Among the diverse landscape of leadership styles, one established framework, which is focused on one’s own leadership practice with an immediate group and thus most relevant for this setting, categorizes leadership into four distinct styles: authoritative, democratic, facilitative, and situational (National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde). In an authoritative leadership style, leaders assume personal responsibility for decisions, making decisions and then presenting those decisions to the group (National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde). In a democratic leadership style, leaders establish a structure and ground rules and try to include all group members in decision-making (National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde). In a facilitative leadership style, leaders offer suggestions, which group members may or may not apply (National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde). In groups led by facilitative leaders, structure, content, and operation of the group are left to group members to agree upon (National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde). In a situational leadership style, leaders attempt to adapt to the needs of the situation, varying their style so that it is appropriate for the current group (National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde). For community coalitions, such as CEBEC initiatives, a sharing/collaborative/empowering (Kumpfer, 1993) leadership style may be most effective (Alexander, 2006).

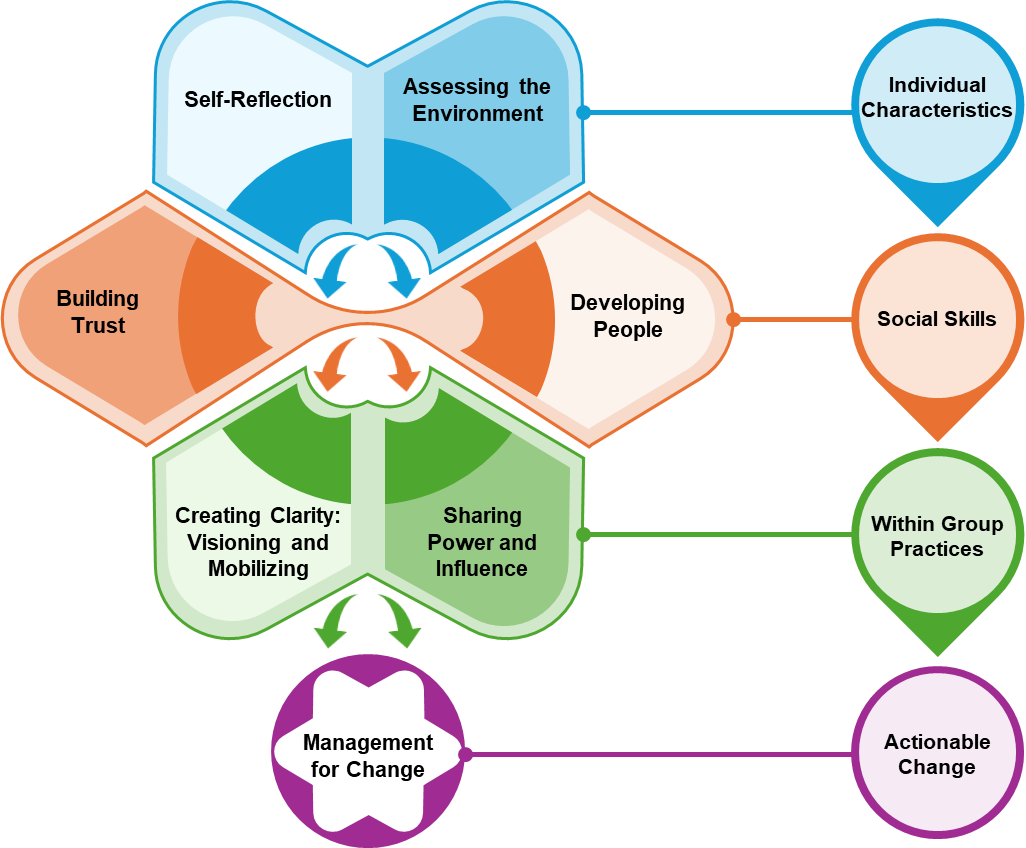

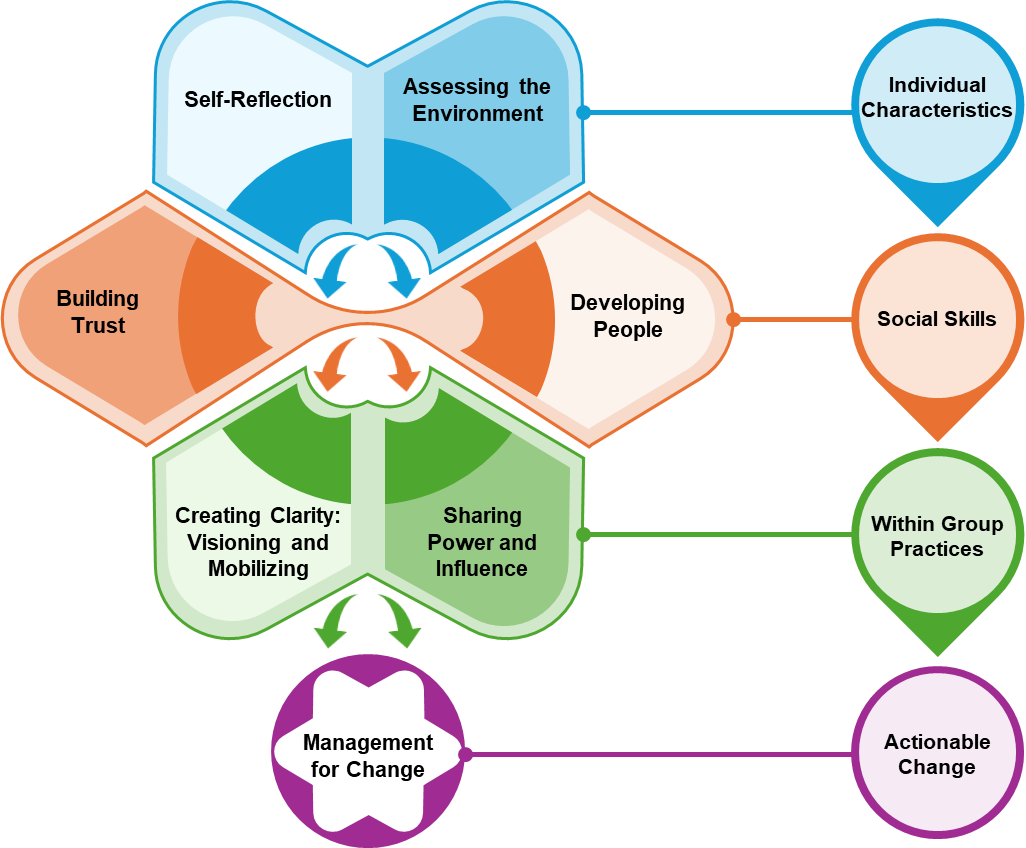

Effective community health coalitions or civic engagement groups thrive under leaders equipped with specific collaborative leadership skills. Recommended collaborative leadership skills for improved health outcomes include assessing the environment (e.g., using assessment tools to understand the needs of the community), visioning and mobilizing (e.g., facilitating the development of a shared community vision), building trust (e.g., using communication practices that make people feel safe sharing), sharing power (e.g., offering people an active role in decision-making), helping people develop (e.g., helping people take advantage of new opportunities), and self-reflection (e.g., working to understand other people’s perspectives) (Turning Point, 2001, 2002) Supplemental Figure 1 depicts how these collaborative leadership skills as the individual characteristics impact social skills, which in turn impact group practices to facilitate actionable change within health coalitions or civic engagement groups (Miller, 2009).

Figure 1. Collaborative Leadership Skills Model for Actionable Change

|

Successful community-based health programs are often fueled by leaders who can unite participants towards a shared vision while promoting personal and professional growth in their members (Estabrooks, 2004; University of Kansas Center for Community Health and Development). By empowering participants and supervising program implementation effectively, leaders can significantly influence program success (Estabrooks, 2004). Understanding leadership style and necessary skills is critical for improving trainings to build the capacity of the community and to achieve positive health outcomes beyond data collection and program implementation (Grimm, 2022). A study on Community Health Agents reported how women in these community health leadership roles felt empowered and valued as leaders and felt comfort in expressing their agency in community decision making (Allen, 2022). The study highlighted a cultural shift in community-based health programs, with leaders acting as catalysts and mobilizing members and residents to empower each other. These leaders fostered a sense of collective investment in individual and community-wide health.

A democratic leadership style and excellent collaborative leadership skills may be most effective for coalition work and health promotion like CEBEC interventions since community members are actively engaged and also leading the projects (Seguin et al., 2018). Additionally, training in collaborative leadership styles can help groups improve in functioning and collaboration (Kim, 2017).

We hypothesized that Agents, who volunteered to lead CEBEC project groups, would have a democratic leadership style and score relatively high in most collaborative leadership skills. If we found that they did not have a democratic leadership style or did not score relatively high in most collaborative leadership skills, it may be worth considering adding training to encourage this leadership style and improve collaborative leadership skills to the CC curriculum to position CCs for maximum effectiveness. Future public health interventions, particularly CEBEC interventions, rural-based programs, and Extension-based programs, may also benefit from surveying their leaders to understand leadership style and collaborative leadership skills.

Methods

This research was conducted as a part of an evaluation of the CC program, a cluster randomized controlled trial in 12 communities across two states (Texas and New York) using a two-arm parallel design, described in detail elsewhere (Seguin-Fowler et al., 2022). For this report, cross-sectional analysis of baseline data were used to categorize program facilitators’ leadership styles and score their collaborative leadership skills.

Sample

Seven county-level Agents participating in the CC evaluation as program facilitators were surveyed at baseline, prior to any program training or implementation. Agents were selected based on their community meeting study inclusion and exclusion criteria and their willingness to participate as educators. Descriptive details on the Agents were collected by review of online biographies, LinkedIn profiles, and publicly available news articles on the Agents. Leadership surveys were self-administered online instruments collected via Qualtrics. Data were then reviewed by research staff and Agents for accuracy. The study was approved by the Texas A&M Institutional Review Board (protocol # IRB2021-1490).

Leadership measures and analysis

Agents were invited via email to complete a survey that contained questions from two tools for assessing leadership style and collaborative leadership skills. The format of both tools in their original formats are that an individual self-rates using the questionnaires and then scores the questionnaires as instructed and then reviews how they are categorized based on the scores. The study team modified that process, following the same scoring procedures but not sharing the individual scores with the Agents.

Leadership style

The 16-item tool from the National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde (National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde) was included to assess the four leadership styles. The research team selected this tool after reviewing multiple other similar surveys and deemed the survey to be comprehensive with minimal respondent burden. The survey contained four questions related to each of the four leadership styles: 1) authoritative; 2) democratic; 3) facilitative; 4) situational. Authoritative style is characterized by leaders assuming personal responsibility for decisions. Facilitative is described as a leader who commonly offers suggestions that group members may or may not adopt. Democratic style is known for inclusion of all group members in decisions about how the group should operate. Situational is a style known for adapting to the needs of each situation. The democratic leadership style is the most collaborative conceptually and the authoritative style is least collaborative. Each question response is associated with a score from 0-3 (0=‘not like me at all,’ 1=‘a bit like me,’ 2=‘much like me,’ 3=‘exactly like me’) (Supplemental Table 1). For analysis, the scores were tallied for each response selected and summed in relation to each corresponding leadership style. The highest score a respondent could receive for each of the leadership styles was 12. We reported on the style with the highest score for each leader, or in cases where they were tied, the top two.

Table 1. Leadership style definitions and associated survey items

|

Leadership Style |

Definition |

Survey Items |

|

Authoritative |

An authoritative leader assumes responsibility for decisions, defines necessary objectives, and acts. They make quick decisions and can consult with the group beforehand or communicate after the decision has been made. This is the least collaborative style. |

I’m happy to act as the spokesperson for our group. I’m determined to push projects forward and get results. I am good at organizing other people. I set myself high standards and expect others to do the same for themselves. |

|

Democratic |

A democratic leader values group participation and allows members to weigh in on decisions. They establish structure to enable and encourage group members and their individual responsibility. This is the most collaborative leadership style. |

I believe teams work best when everyone is involved in making decisions. I enjoy working on committees. I don’t mind how long discussions last, so long as we consider every angle. I think all group members should abide by formal decisions, so long as we follow proper procedures. |

|

Facilitative |

A facilitative leader values teamwork and leaves the structure and organization to be determined by the group. They do not allow their personal opinions to influence the group and support the journey of learning. This is the second most collaborative leadership style. |

I’m good at bringing out the best in other people. I think people should be allowed to make mistakes in order to learn. I think the most important thing for a group is the well-being of its members. I love helping other people to develop. |

|

Situational |

A situational leader adapts their behavior to the situation to meet the needs of the team or individual members. Their leadership style can vary depending on the skill level of the group or task at hand. This is the third most collaborative leadership style. |

I can take on a leadership role when needed, but don’t consider myself a ‘leader.’ I’m good at adapting to different situations. I can see situations from many different perspectives. I enjoy role-playing exercises. |

Collaborative leadership skills

Collaborative leadership skills were measured in the survey by using the Turning Point Collaborative Leadership Self-Assessment Questionnaire (Turning Point), which evaluated key behaviors within the six skills of effective collaborative leaders. Each scale had 10-11 items on a 1-7 scale (from 1=seldom to 7=almost always) (Table 2). For analysis, the survey instructions indicate that each scale should be totaled and grouped into the following categories: Excellent Score (61-70), Stronger Score (41-60), Opportunities for Growth (21-40), and Important to Change Behavior (1-20). We then compiled the percentage of Agents who scored within each of the categories by skill, as well as comparing the category rankings across all skills by Agent. Each collaborative leadership skills subscale, for example assessing the environment, also had two open-ended questions that provided additional details regarding strengths and areas for improvement. The analysis was based on rigorous and accelerated data reduction (RADar) (Allen, 2022) and the responses from two open-ended questions for each subscale were pasted into a Word document. Then the experienced researchers highlighted words and phrases that stood out, distilled those down into a main idea, and then compared across responses for consistency and exceptions. One exemplar quote was selected if there was consistency across responses. Two exemplar quotes were selected if the responses were divergent.

Table 2. Collaborative leadership skill measures and example survey items

|

Leadership Skills |

Definition |

Example Survey Items |

|

Assessing the Environment |

Leaders must understand the context of a situation before they can decide when or how to act. |

I use a systems perspective to understand the community.

I encourage people to act on information rather than assumptions.

I look at the perceived problem from different angles before proceeding. |

|

Creating Clarity: Visioning and Mobilizing |

Leaders should find clarity in their purpose towards the group and its goals, allowing members to establish a shared vision and encouraging them to act upon their goals. |

I facilitate an effective process for exploring the diverse aspirations among community stakeholders. I communicate the shared vision broadly.

I build an action plan with timelines and assigned responsibilities to enable the community vision to be achieved. |

|

Building Trust |

Leaders must build trust among the members of the group to build a foundation for successful collaboration. |

I build communication processes that make it safe for people to say what is on their minds.

I “walk the talk,” i.e., I do what I say I will do.

I protect the group from those who would wield personal power over the collaborative process. |

|

Sharing Power and Influence |

Leaders should recognize how sharing power with group members will increase power and ensure a successful collaboration process that decentralizes individual achievement. |

I offer people an active role in decision making about matters that affect them.

I use my personal power responsibly to encourage others to act together to change circumstances that affect them.

I share power with others whenever possible. |

|

Developing People |

Leaders must bring out the best in others by encouraging their opportunity building and success. Leaders who encourage members to increase their potential build confidence within the group. |

I take seriously my responsibility for coaching and mentoring others.

I invest adequate amounts of time doing people development.

I help people take advantage of opportunities to learn new skills. |

|

Self-Reflection |

Leaders must self-reflect to understand how their actions and behaviors align. They must understand the impact of their behavior on the group. |

I recognize the effect of my emotions on work performance.

I listen to others actively, checking to ensure my understanding.

I recognize my personal impact on group dynamics.

I work to understand others’ perspectives. |

We also examined level of collaborative skills across leadership styles. Conceptually, an authoritative leadership style is the least collaborative, and we anticipated lower mastery of collaborative skills for Agents with this primary leadership style and higher mastery within other leadership styles.

Results

All seven invited Agents completed the survey; all were women. Of the Agents who completed the survey, four had a bachelor’s degree and three had a master’s degree. The Agents had worked in their roles for a mean of 11 years (ranging from 3 to 22 years). Those with a master’s degree had an average of 10 years’ experience (ranging from 3 to 22 years). Those with a bachelor’s degree had an average of 11 years’ experience (ranging from 7 to 16 years).

Leadership styles of CC Agents

The leadership styles of the CC Agents are shown in Table 1. Notably, four Agents had two styles that were tied as their highest score. Authoritative was the leadership style reported by the majority of Agents (n=4, 57%). Facilitative (n=3, 43%) was the second most common style. Democratic and Situational were both represented in two Agents.

Table 1 is organized from most authoritative at the top to least authoritative score at the bottom. Those who scored highly authoritative were less likely to be situational leaders. Reversely, those who scored highest as situational leaders were less likely to be authoritative leaders. Agents with a bachelor’s degree rated themselves higher on all four leadership styles compared to those with a master’s degree. Those with less than 10 years of experience scored highly in the authoritative leadership style (9 vs 7.5). Those who had more than 10 years of experience scored higher in facilitative leadership style than those with less than 10 years’ experience (9.5 vs 8). More experienced Agents also scored higher on the situational leadership style (8.5 vs 6.67). Three out of the four Agents based in Texas scored highly in the authoritative leadership style. Both Agents who scored highly in the democratic leadership style were in Texas.

Table 3. Leadership style scores of the Change Club Agents (n=7)

|

Agent |

Authoritative |

Democratic |

Facilitative |

Situational |

|

1 |

12 |

5 |

12 |

9 |

|

2 |

10 |

10 |

9 |

8 |

|

3 |

9 |

7 |

8 |

7 |

|

4 |

8 |

8 |

7 |

5 |

|

5 |

7 |

9 |

8 |

10 |

|

6 |

6 |

9 |

12 |

9 |

|

7 |

5 |

5 |

6 |

6 |

|

All Agents, mean (range) |

8 (5-12) |

8 (5-10) |

9 (6-12) |

8 (5-10) |

|

Agents with a master’s degree, mean (range) |

7.33 (5-12) |

6.67 (5-8) |

7 (6-8) |

6 (5-7) |

|

Agents with a bachelor’s degree, mean (range) |

8.75 (6-12) |

8.25 (5-10) |

10.25 (8-12) |

9 (8-10) |

|

Agents with 10 or more years Extension experience, mean (range) |

7.5 (5-12) |

7 (5-9) |

9.5 (6-12) |

8.5 (6-10) |

|

Agents with less than 10 years Extension experience, mean (range) |

9 (8-10) |

8.33 (7-10) |

8 (7-9) |

6.67 (5-8) |

Note: Color scale from darker blue=highest score within Agent to lightest blue=lowest score within Agent.

Collaborative leadership skills of CC Agents

In terms of collaborative leadership skills, Agents mainly scored in the Excellent Score or Stronger Score range for all six skills (Figure 2). Most Agents had an Excellent Score in assessing the environment (n=4), sharing power and influence (n=5), and developing people (n=5). The highest proportions in the Stronger Score category were for creating clarity (n=4); building trust (n=4), and self-reflection (n=4). Assessing the environment and creating clarity had one Agent in each that scored in the Opportunities for Growth range.

Figure 2. Collaborative Leadership Skills Across Educators

For each Agent, self-ratings of collaborative leadership skills are shown in Figure 2. Only one Agent rated herself as Excellent Score across all collaborative leadership skills. Another Agent rated herself as Stronger across all skills. Only one Agent indicated that she had collaborative leadership skill areas where she had opportunities for growth (n=2, assessing the environment and creating clarity). There were small differences observed between Agents with 10+ years of experience compared to Agents with less experience; and between the Agents in Texas and New York. No observed differences were statistically significant. Overall, all Agents self-rated themselves highly for their collaborative leadership skills.

Figure 3. Collaborative Leadership Skills For Each Educator

Agents whose primary leadership style was authoritative rated themselves Excellent Score for the collaborative skills most of the time (Table 2). Within the primary authoritative style, only for one collaborative leadership skill, creating clarity, were Stronger Score and Opportunities for Growth indicated, though that skill is the one that appears the lowest across all leadership styles. The democratic leadership style (most collaborative style) did not exist as a sole primary style and when Agents scored highly on the democratic style, they also scored highly on the authoritative style. Thus, like the authoritative style, the democratic style scored Excellent Score for the collaborative leadership skills often. The facilitative leadership style had one Agent with solely that primary style and the same is true for the situational style. Both of those styles, which are less collaborative than the democratic, but more collaborative than the authoritative style, indicated Stronger Score for most of the collaborative leadership skills.

Table 3. Change Club Agents’ primary leadership styles and their collaborative leadership skills scores

|

Skill |

Authoritative |

Democratic |

Facilitative |

Situational |

|||||||

|

Agent |

3 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

2 |

6 |

7 |

1 |

5 |

7 |

|

Assessing the Environment |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

= |

+ |

+ |

= |

+ |

|

Creating Clarity |

= |

- |

+ |

= |

- |

+ |

= |

+ |

= |

= |

+ |

|

Building Trust |

+ |

= |

+ |

+ |

= |

+ |

= |

= |

+ |

= |

= |

|

Sharing Power and Influence |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

= |

+ |

|

Developing People |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

= |

+ |

|

Self-Reflection |

+ |

= |

+ |

+ |

= |

+ |

= |

+ |

+ |

= |

+ |

Note: + Excellent score; = Stronger Score; - Opportunities for Growth; Agents who had two primary leadership styles are shown twice.

For the open-ended questions about their strengths and improvement areas for each of the six collaborative leadership skills, Agents generally mentioned similar strengths, but had more varied responses regarding areas for improvement (Tables 4 and 5). The tables are organized by each skill to reflect the way that the open-ended questions were asked directly after each skill’s question items. Consistent themes from the Agents’ perceived strengths across the skills included communication and listening, openness, inclusiveness, facilitation and consensus building, and encouragement/support. The Agents’ areas for improvement across the skills highlighted the challenges they often faced as Agents, especially regarding limited time and resources, and the difficulties in coordinating partners and getting community buy-in and active participation in projects. While a few areas mentioned were knowledge-based, such as data analysis, technology, or coaching plans, most improvement areas mentioned focused more on not overcommitting/promising, protecting time and boundaries, delegation, and seeking regular feedback.

Table 4. Collaborative Leadership Skills Open-Ended Questions Summary

|

|

Strengths |

Areas for Improvement |

|

Assessing the Environment |

Most Agents highlighted their open-mindedness and good listening skills as strengths, especially regarding inclusiveness and respecting multiple perspectives. They also highlighted their many years of experience and familiarity/comfort as a key strength. |

Responses varied but several of the Agents thought data analysis was an area for improvement, as well as better community connections and ensuring buy-in. Other areas mentioned were needing more knowledge, protecting their time and commitments, and time efficiency. |

|

Creating Clarity: Visioning and Mobilizing |

Agents agreed that their strengths lay in having and communicating a strong/shared vision, effective facilitation, and organization. |

Most Agents expressed concerns around engagement, either with understanding of complex concepts, interest and buy-in, or sense of ownership. One Agent noted that it is easy to feel discouraged with low resources and low interest in the community. |

|

Building Trust |

Several Agents noted how critical or foundational trust and relationships are to success and that they enjoy this aspect of the work. Some specific strengths noted were ethics and interpersonal skills such as effective communication, honesty and openness, respect, inclusiveness, and safety. |

Agents varied in their areas for improvement for building trust and fostering relationships, with one noting technology as one area, and another noting staying persistent in communication and follow-ups. A few Agents mentioned overcommitment or doing too much. |

|

Sharing Power and Influence |

Responses focused around fostering self-confidence and decision-making, openness, listening, and making others feel needed. Other responses included facilitating consensus building and creativity. |

Agents thought there was room for improvement in empowerment, letting others do tasks or make decisions, or in balance of power, not giving up too much and holding their ground as a leader when needed. |

|

Developing People |

Overall, most Agents said their strengths were in encouragement and uplifting others, helping them develop self-confidence and their skills and talents. They noted providing coaching/mentoring and providing clear expectations, feedback, and support as other strengths. |

Agents noted that improvement areas are in their own self-confidence, formally defining expectations or coaching plans, and establishing norms for giving/receiving feedback. They also noted that delegating tasks and solutions so that others can learn and build skills when it may be faster to do it for them were an area of improvement. |

|

Self-Reflection |

Some Agents noted either a willingness to self-reflect or that they do it often, that they are aware of group dynamics, or good at reading people. Others noted listening as a strength, and one Agent said that they don’t make decisions based on emotions. |

Most Agents shared that they struggled either with giving or receiving feedback and that they could seek it out more, either from peers or self-assessment tools. Others noted either needing more patience, paying attention to their own needs, or being more positive to themselves. |

Table 5. Collaborative Leadership Skills Open-Ended Questions Exemplar Quotes

|

|

Strengths |

Areas for Improvement |

|

Assessing the Environment |

“I have an open mind and enjoy motivating and encouraging others to take ownership of a project. I am a good listener and do my best to make sure everyone is heard and recognized for their contributions.”

“I have a lot of experience working on environmental change projects and am comfortable with the process.” |

“Data collection and analysis: Improving the quality and quantity of environmental data and developing better methods for analyzing and interpreting that data.”

“I think the hardest part is aligning and empowering members to participate in the assessment process.” |

|

Creating Clarity: Visioning and Mobilizing |

“I have facilitated various groups and committees and worked towards a shared vision and action plan. I have facilitated effectively and the groups made great strides towards their goals.” |

“…it is hard to think positively knowing the lack of resources in both communities. It has also been hard to develop interest and achieve buy-in from community members in terms of any positive health changes.” |

|

Building Trust |

“I see building trust as the foundation for collaboration. I create environments that are safe for all stakeholders to contribute.” |

“I think communication is challenging in this work because it is often not a top priority with other partners and so you often have to send friendly reminders, circle back, try to set deadlines, etc. This can feel awkward sometimes but you have to be willing to be persistent in order to ensure goals are met.”

“I am always doing more than I need to do.” |

|

Sharing Power and Influence |

“I believe the most effective leaders are the ones who encourage and foster self-confidence in others. I encourage participants to take an active role in making decisions.” |

“It can be tempting to want to jump in and offer answers or opinions. Encouraging others to provide these instead of me can sometimes be a challenge.”

“I may be too open and influenced by what others think. I need to work on standing my ground with large personalities.” |

|

Developing People |

“I take my role as a leader seriously and genuinely want others to feel uplifted and better for being part of my team. I look for ways for others to build their skills and talents.” |

“Creating an environment where giving and receiving regular feedback is the norm is still somewhat of a challenge…I've also been prone to giving out answers rather than empowering staff to discover answers on their own.” |

|

Self-Reflection |

“I regularly self-reflect and have a pretty good handle on my strengths and weaknesses.” |

“I don't always seek out feedback as often as I could.” |

Discussion

Certain leadership styles and skills may relate to more effective coalitions and health promotion programs (Turning Point, 2001, 2002). The majority of CC Agents reported an authoritative style, tempered by high or equivalent scores on at least one other style. While none of the Agents reported only a democratic leadership style, which is the most collaborative, the two Agents who scored highly on democratic leadership style also scored highly on authoritative leadership style. Having multiple leaderships styles based on the four types used in this study may not be unlikely, as there are qualities from each that are observed in other successful Extension Agents. For example, the five most prevalent leadership styles found in Florida Extension Agents using the validated Leadership Practices Inventory were challenging the process, enabling others, inspiring a shared vision, encouraging others, and modeling the way (Rudd, 2000). Challenging the process aligns with authoritative leadership style, enabling others and encouraging others align with facilitative leadership style, inspiring a shared vision aligns with democratic leadership style, and modeling the way aligns with situational leadership style. Considering the possibility for leaders to have multiple styles of leadership, training for future Extension Agents may instead emphasize the specific collaborative leadership skills highlighted in this paper.

Agents generally scored highly on all collaborative leadership skills, with primarily authoritative leaders more often indicating that they were highly skilled in collaborative leadership skills. While this may be counterintuitive, the listed collaborative leadership skills are distinct from the four leadership styles. Many of the listed skills align with the recommended servant leadership model, which was proposed as guide for Extension programs in the 21st century (Astroth, 2011). Creating clarity was the skill often rated less than excellent. This finding may relate to the unique challenge of health interventions and the need to set a clear, specific goal and vision for successful implementation. In a similar study asking about training needs of Extension Agents in Tennessee, “creating vision” was a skill identified by Family & Consumer Science Agents (Hall, 2016) that they needed additional training in. Game-based learning has been shown to be an effective technique to train individuals on new leadership skills and styles (Sousa & Rocha, 2019).

Overall, this sample of Extension Agents were confident in the collaborative leadership skills that are associated with health outcomes (Turning Point, 2002). Most Agents rated themselves with an Excellent Score on most skills, so only minimal improvements in collaborative leadership skills may be expected from CC intervention training or from the facilitation of the CC program. This may be due to the existing leadership skills that are necessary for an Extension Agent role. In an assessment of training needs for Extension Agents in Florida, building positive relationships with individuals and groups was perceived as the most important and most proficient leadership quality (Harder, 2019). This quality relies on multiple collaborative leadership skills identified in this paper, such as building trust, sharing power and influence, and developing people. Therefore, the leadership qualities of Extension Agents may be equally strong. Given that there was not much variability across the Agents, it will be difficult to assess whether their leadership skills impact group process and overall health outcomes. Through the planned mixed methods process evaluation, which includes semi-structured interviews with the Agents, we will take collaborative leadership skills into consideration for understanding the CC program implementation and effects.

There are several notable limitations to this study. All data were self-reported and neither of the questionnaires have been validated. Although there are validated leadership surveys and frameworks available (Meynhardt et al., 2023; Rosenbloom & Ash, 2010), this survey was selected because it was expected to be sensitive to change over time. Second, response bias due to years of experience or education are unknown and limit our ability to make conclusions related to the small differences observed in leadership style according to experience and education. The high number of skills rated as excellent may also represent social desirability or inflated self-efficacy. Third, the number of Agents surveyed is small and likely biased toward collaborative styles and skills given their self-selection into a CEBEC intervention (which is collaborative by design). Finally, all Agents in this sample were female, and these results may not be generalizable to male Agents.

In future work, this research team will collect longitudinal leadership data to understand whether Extension Agents’ leadership styles and skills are associated with successful implementation of this CEBEC intervention. We will also collect both qualitative and quantitative data to explore whether any particular leadership style, combination of leadership styles, or particular collaborative leadership skills are associated with group processes, completion of certain tasks, overall effectiveness, or sustainability of outcomes. Future studies of leadership characteristics should include larger numbers of Agents delivering CEBEC interventions and other types of Extension programming.

Correspondence should be addressed to

Rebecca A. Seguin-Fowler

Institute for Advancing Health Through Agriculture

Texas A&M University

1500 Research Parkway, Centeq Building B, Suite 270

College Station, TX 77845, United States

![]() Meredith

L. Graham: 0000-0001-8989-1417

Meredith

L. Graham: 0000-0001-8989-1417

![]() Elena

Andreyeva: 0000-0002-8644-4264

Elena

Andreyeva: 0000-0002-8644-4264

![]() Sara

C. Folta: 0000-0002-4366-5622

Sara

C. Folta: 0000-0002-4366-5622

![]() Karla

L. Hanson: 0000-0003-1013-4021

Karla

L. Hanson: 0000-0003-1013-4021

![]() Jay

E. Maddock: 0000-0002-1119-0300

Jay

E. Maddock: 0000-0002-1119-0300

Rebecca A. Seguin-Fowler: 0000-0002-5115-2341

Funding

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (R01CA230738).

Editor

Justin Moore served as the editor for this article.

Acknowledgements

Extension Agents, Change Club study participants, Deyaun Jafari, Grace Marshall, and Leah Volpe.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: RASF. Methodology: MLG. Writing – Original Draft: MLG. Writing – Review & Editing: MLG, GDE, MD, MK, AC, VL, EA, SCF, KLH, JEM, RASF.

Competing interests

Rebecca A. Seguin-Fowler is the owner of StrongPeople, LLC. No other authors have financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

References

Adams, A. K., Scott, J. R., Prince, R., & Williamson, A. (2014). Using community advisory boards to reduce environmental barriers to health in American Indian communities, Wisconsin, 2007-2012. Preventing Chronic Disease, 11, Article E160. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd11.140014

Alexander, M. P., Zakocs, R.C., Earp, J.A., French, E. (2006). Community coalition project directors: what makes them effective leaders? Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 12(2), 201-209.

Allen, E. M., Frisancho, A., Llanten, C., Knep, M.E., Van Skiba M.J. (2022). Community Health Agents advancing women's empowerment: a qualitative data analysis. Journal of Community Health, 47(5), 806-813.

American Psychological Association. Civic Engagement. https://www.apa.org/education-career/undergrad/civic-engagement

Astroth, K. A., Goodwin, J., Hodnett, F. (2011). Servant leadership: guiding Extension programs in the 21st Century. Journal of Extension, 49(3).

Barnidge, E. K., Baker, E. A., Estlund, A., Motton, F., Hipp, P. R., & Brownson, R. C. (2015). A participatory regional partnership approach to promote nutrition and physical activity through environmental and policy change in rural Missouri. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12, Article E92. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.140593

Berkowitz, B. (2000). Collaboration for health improvement: models for state, community, and academic partnerships. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 6(1), 67-72.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Strategies to Prevent Obesity and Other Chronic Diseases: The CDC Guide to Strategies to Increase Physical Activity in the Community.

Estabrooks, P. A., Munroe, K.J., Fox, E.H. et al. (2004). Leadership in physical activity groups for older adults: a qualitative analysis. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 12(3), 232-245.

Gavin, V. R., Seeholzer, E. L., Leon, J. B., Chappelle, S. B., & Sehgal, A. R. (2015). If we build it, we will come: a model for community-led change to transform neighborhood conditions to support healthy eating and active living. American Journal of Public Health, 105(6), 1072-1077. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2015.302599

Grimm, B., Ramos, A.K., Maloney, S., et al. (2022). The most important skills required by local public health departments for responding to community needs and improving health outcomes. Journal of Community Health, 47(1), 79-86.

Hall, J. L., Broyles, T.W. (2016). Leadership competencies of Tennessee Extension Agents: implications for professional development. Journal of Leadership Education, 15(3).

Hansen, A. Y., Meyer, M. R. U., Lenardson, J. D., & Hartley, D. (2015). Built environments and active living in rural and remote areas: a review of the literature. Current Obesity Reports, 4(4), 484-493.

Harder, A., Narine, L.K. (2019). Interpersonal leadership competencies of Extension Agents in Florida. Journal of Agricultural Education, 60(1).

Hinckson, E., Schneider, M., Winter, S. J., Stone, E., Puhan, M., Stathi, A., Porter, M. M., Gardiner, P. A., dos Santos, D. L., Wolff, A., & King, A. C. (2017). Citizen science applied to building healthier community environments: advancing the field through shared construct and measurement development. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14, Article 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0588-6

Hoffman, D. (2022). Commentary on Chronic Disease Prevention in 2022. https://chronicdisease.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/FS_ChronicDiseaseCommentary2022FINAL.pdf

Kim, J. Y., Honeycutt, T., Morzuch, M. (2017). Transforming coalition leadership: an evaluation of a collaborative leadership training program. The Foundation Review, 9(4).

Kumpfer, K. L., Turner, C., Hopkins, R., Librett, J. (1993). Leadership and team effectiveness in community coalitions for the prevention of alcohol and other drug abuse. Health Education Research, 8(3), 359-374.

Lewin, K., Lippitt, R. White, R.K. (1939). Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created "social climates." Journal of Social Psychology, 10(2).

McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351-377. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401

Meynhardt, T., Steuber, J., & Feser, M. (2023). The Leipzig Leadership Model: Measuring leadership orientations. Current Psychology, 43(10), 9005-9024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04873-x

Miller, W. R., Miller, J.P., . (2009). Leadership styles for success in collaborative work. http://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/316071/Tamarack_New_Website/success_in_collaborative_work.pdf?t=1467765739074

National Association of County and City Health Officials. (September 2018). Local Implementation and Capacity of Cancer Prevention and Control: A National Review of Local Health Department Activities. https://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Cancer_Survey_Report_9.2018.pdf

National Health Service of Greater Glasgow and Clyde. Leadership Styles Questionnaire. Retrieved April 3 from https://www.nhsggc.org.uk/media/262878/leadership-questionnaire-fillable.pdf

Rosenbloom, J. L., & Ash, R. A. (2010). Professional Worker Career Experience Survey, United States, 2003-2004 Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR26782.v1

Rudd, R. (2000). Leadership styles of Florida's County Extension Directors: perceptions of self and others. (pp. 81-92). Proceedings of the 27th Annual National Agricultural Education Research Conference.

Schwarte, L., Samuels, S. E., Capitman, J., Ruwe, M., Boyle, M., & Flores, G. (2010). The Central California Regional Obesity Prevention Program: changing nutrition and physical activity environments in California's heartland. American Journal of Public Health, 100(11), 2124-2128.

Seguin, R. A., Sriram, U., Connor, L. M., Silver, A. E., Niu, B., & Bartholomew, A. N. (2018). A civic engagement approach to encourage healthy eating and active living in rural towns: the HEART Club pilot project. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32(7), 1591-1601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117117748122

Seguin-Fowler, R., Graham, M., Demment, M., MacMillan Uribe, A., Rethorst, C., & Szeszulski, J. (2024). Multilevel interventions targeting obesity: state of the science and future directions. Annual Review of Nutrition. 44(Volume 44, 2024):357-81.

Seguin-Fowler, R. A., Hanson, K. L., Villarreal, D., Rethorst, C. D., Ayine, P., Folta, S. C., Maddock, J. E., Patterson, M. S., Marshall, G. A., & Volpe, L. C. (2022). Evaluation of a civic engagement approach to catalyze built environment change and promote healthy eating and physical activity among rural residents: a cluster (community) randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1-17.

Sheats, J. L., Winter, S. J., Romero, P. P., & King, A. C. (2017). FEAST: empowering community residents to use technology to assess and advocate for healthy food environments. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 94(2), 180-189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0141-6

Turning Point. Collaborative leadership: self-assessment questionnaire. Retrieved April 3 from https://cdn2.hubspot.net/hubfs/316071/Resources/Article/Collaborative_Leader_self-assessments.pdf

Turning Point. (2001). Collaborative Leadership and Health: A Review of the Literature. http://216.92.113.133/Pages/pdfs/lead_dev/devlead_lit_review.pdf

Turning Point. (2002). Academics and Practitioners on Collaborative Leadership. http://216.92.113.133/Pages/pdfs/lead_dev/LDC_panels_lowres.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture, N. I. o. F. a. A. Cooperative Extension System. Retrieved April 3 from https://www.nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa/how-we-work/extension/cooperative-extension-system

University of Kansas Center for Community Health and Development. Styles of Leadership. In Community Tool Box. Retrieved April 3 from https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/leadership/leadership-ideas/leadership-styles/main

Willett, W. C., Koplan, J.P., Nugent, R., Dusenbury, C., Puska, P., Gaziano, T.A. (2006). Prevention of Chronic Diseases by Means of Diet and Lifestyle Changes. In D. T. Jamison, Breman, J.G., Measham, A.R., et al. (Ed.), Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries (2nd ed.). The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank.

World Health Organization. (2003). Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (0512-3054). (WHO Technical Report Series, No. 916).