Figure A.

Frederick Law Olmsted's Original Buffalo Parks System – (Designed 1868; Drawn

1876)

Complete Highway Removal vs. Highway Removal to Boulevards vs. Caps: Redressing

Past Wrongs while Addressing the Decay of America’s Most Ambitious Public Works Project

Brad Wales1 and Jennifer D. Roberts2

1Department of Architecture, University at Buffalo, School of Architecture and Planning, Hayes Hall, U.S.A.

2Department of Kinesiology, University of Maryland, School of Public Health, U.S.A.

Reconnecting The Best Planned City

This is a moment in time, a crossroads even, when public planning processes will either continue to capitulate to the unilateral assumption of retaining existing highways, expressways and transportation corridors, or to insist on a common sense case-by-case approach whereby a clean slate evaluation is started for every transportation project. In Buffalo, New York, where thousands of lives and billions of dollars in future urban developments are at stake, an unbiased approach to evaluating crumbling transportation infrastructures has become an urgent and critical need. In particular, the Kensington Expressway - Route 33 (hereinafter referred to as “Expressway”) is at an advanced age; it was initially constructed as an urban renewal and racism-by-design highway that gutted the East Side of Buffalo in the 1960s. The East Side, an area that is home to over 80% of all Black Buffalonians, was once graced with the Humboldt Parkway. Landscaped by Frederick Law Olmsted, who proclaimed Buffalo to be “the best planned city, as to streets, public places, and grounds, in the United States, if not in the world,” Humboldt Parkway was an idyllic greenscape and oasis for recreation, fellowship, and active living that was demolished and replaced by the Expressway (Figure A) (Supplemental Figure 1, 2) (Kowsky & Carr, 2018).

Figure A.

Frederick Law Olmsted's Original Buffalo Parks System – (Designed 1868; Drawn

1876)

Now, the Expressway is a constant source of noise and air pollution. These environmental hazards are deleterious to human health and wellbeing and are an on-going detriment to sustainability and efforts to combat the climate crisis. Specifically, fine particulate matter (PM2.5), a modulator and contributor of the climate crisis, is 26% to 28% above average on the East Side compared to the entire Buffalo and Niagara region (Park et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021; NYSDEC, 2024; McAndrew, 2024; Shuman, 2024). Vehicular emissions, including PM2.5, have contributed to disparately high rates of chronic diseases and illnesses, such as asthma, heart disease, cancers, mental disorders, and even a five to ten year shorter life expectancy among Black vs. White Buffalo residents (Yoo & Roberts, 2024; Murphy et al., 2022). The University at Buffalo (UB) Department of Architecture Small Built Works class documented these conditions specifically to Humboldt Parkway neighborhoods using the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Environmental Justice Screen Tool (Supplemental Figure 3-5 and 9). Furthermore, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) just released the Community Air Quality Initiative conducted in 2021-2022. This report revealed that levels of PM2.5 are highest in Buffalo and “Above Focus Spot Threshold” especially in Hamlin Park and Trinidad, neighborhoods that straddle the Expressway and Scajaquada Expressway - Route 198 (Supplemental Figure 6) (McAndrew, 2024). Just last year, the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) released the Expressway Draft Design Report/Environmental Assessment (DDR/EA) and in Appendix D7 projected vehicle exhaust plumes were depicted spewing 900-feet out each portal end (Supplemental Figure 7). The UB Small Built Works class overlaid these NYSDOT’s projected plumes back onto the neighborhoods with pin-mapped locations of schools, churches, medical, and youth facilities (Supplemental Figure 8).

These stakes and costs, namely the health of East Side communities, are too high to default to a one-size-fits-all approach for highway remediation. Based on these unique set of circumstances in Buffalo, we developed a five tier Transportation Infrastructure Evaluation System (TIES), an objective set of criteria for the remediation and/or maintenance of any given transportation corridor, especially urban highways. “Tier One – Complete Highway Removal” describes what is needed in Buffalo for basic health, and environmental, social, and transportation justice. Building on what we have learned in our own advocacy, this paper presents TIES, which could contribute to a nationwide discussion for setting highway maintenance and evaluation criteria. Additionally, TIES could move the needle towards a standardization of criteria that will be essential for all impending human health and global sustainability issues in the upcoming decades. These intersecting points of concern, although magnifying, are not new. But, in order to fully understand the breadth and depth of said issues, it is necessary to take a step back and review how we got to this point.

U.S. Interstate Highway System

The idea of a U.S. transcontinental highway system originated in the summer of 1919, after Lieutenant Dwight D. Eisenhower participated in the country’s first motor convoy, from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco, California. The young Lieutenant reported some difficulties with the various types of vehicles, like “chain drive trucks,” and explicitly detailed in his November 3, 1919 memorandum the road challenges he encountered throughout the trip.

“It was further observed that some of the good roads are too narrow. This compels many vehicles to run one side off the pavement in meeting other vehicles, shipping the tire, the edge of the pavement and causing difficulty in again mounting the pavement….Extended trips by trucks through the middle western part of the United States are impracticable until roads are improved, and then only a light truck should be used on long hauls….In such cases it seems evident that a very small amount of money spent at the proper time would have kept the road[s] in good condition.” (Eisenhower, 1919)

Lieutenant Dwight D. Eisenhower, November 3, 1919

As a result of inadequate roads and highways, the excursion took over two months to complete, but planted the seed of Eisenhower’s eventual quest for road development and improvement throughout the country. Approximately, 25 years later, Eisenhower was stationed in Germany during World War II where he became enamored by the Reichsautobahnen, a network of freeways with construction initiated under Adolph Hitler’s authority as Chancellor of the Third Reich in 1933. Eisenhower’s vision for a U.S. transcontinental highway system was now resolute, and when he became president, he was determined to make it an actuality. At this point, the U.S. Federal Aid Highway Act of 1944 had already authorized the unfunded construction of a 41,000-mile network of highways throughout the nation, but without federal aid this would be a nearly impossible endeavor for state and local governments. However, three years after becoming the president, Eisenhower signed the U.S. Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. Congress approved a strategy for funding roughly $26 billion. With this strategy, the Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways would be supported and financed with an increased gasoline tax. Eisenhower’s original intent of the Interstate and Defense Highways was to not only facilitate travel between cities, but to also serve as a defense strategy “in case of [an] atomic attack on our key cities, the road net [would] permit quick evacuation of target areas” (U.S.C., 1956). However, throughout the country, these structures were also being built within cities and soon served as physical edifices to perpetuate environmental racism by way of urban renewal, White Flight, residential segregation, and the bifurcation of non-White communities (Reft et al., 2023).

Approaching 70 years in age, the Interstate and Defense Highway System is deteriorating, and in such an advanced state of decay that immediate attention is required in many American cities. For example, in Buffalo, the NYSDOT is so far behind in the maintenance of the Expressway that the massive reinforced concrete retaining walls “have been deteriorating at a rapid rate over the past 5 to 10 years” and are to the point where they cannot be repaired, and must be back-supported by soldier piles, entirely removed, and replaced. Also, “all five of the bridges have…exceeded their expected 40-year service life” by as much as 20-years (Supplemental Figure 12) (NYSDOT, 2023a). The nation’s miles of endless roads for transporting millions of vehicles, often carrying only a single occupant, are also, in many instances becoming obsolete, superfluous and inconsequential. While there are municipalities where the yearly average highway traffic exceeds 100,000 daily vehicles, such as Los Angeles, CA (190,285/day), Miami, FL (122,509/day) and Atlanta, GA (113,440/day), other post-industrial regions, particularly cities in New York State, like Buffalo (31,361/day),[1] Syracuse (28,085/day), and Rochester (39,226/day), do not even reach an average level of 50,000 highway vehicles daily (USDOT, 2021). This begs the question…are these 1950s cold war era, aging, inter- and intra- state highways even necessary? A decision-making process for determining the repair, replacement, or removal of these infrastructures is fully warranted as these highways continue to crumble and reach the end of their anticipated service life. And just as importantly, actions of reparation and atonement are imperative for any level of reconnection in Buffalo and other cities throughout the country that targeted and devasted communities of color with the placement and construction of neighborhood intrastate highways.

White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes

The slogan “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes” encapsulated the opposition of a planned highway, the North Central Freeway, in Washington, D.C (Supplemental Figure 10). In 1967, Sammie Abbott of the Emergency Committee for the Transportation Crisis, stated these words in a testimony before the National Capital Planning Commission. However, Reginald Booker, a young construction worker, anti-freeway activist and social justice leader, leveraged the mantra to galvanize protests against highway construction in Washington, D.C.’s Black neighborhoods. As a child who had been displaced and forced to move, along with 23,000 other residents, due to an urban renewal project, Booker understood the dynamics of race(ism) with regard to urban design and planning.

“The whole freeway situation was predicated on race, economics and militarism… race because the freeway was designed to come through the Black community… economics because it was designed politically and economically to destroy Black communities, especially Black home owners, where most Black people invest most of their money into buying a home.” (Simpson, 2020; Borchardt. 2013)

Reginald Booker, January 25, 1967

Like so many other cities in the U.S., highway expansion from the late 1950s and through the early 1970s, “darkened and disrupted the pedestrian landscape, worsened air quality and torpedoed property values,” and obliterated neighborhoods with the loss of green space, churches, homes, and businesses (Evans, 2021). USDOT estimates that more than 475,000 households and more than a million people were displaced throughout the country because of these highway expansions. Impacted communities, who were predominately Black and often poor, were especially devasted by the loss of small businesses because they provided employment and maintained a local circulation of money. Local commerce was a vital necessity for these communities, who were already weakened by racist zoning policies, disinvestment, and White flight. By design, policymakers and planners used highway construction as a strategy “to raze neighborhoods considered undesirable or blighted and they deployed massive infrastructure elements—multi-lane roadbeds, concrete walls, ramps and overpasses—as tools of segregation [and] physical buffers to isolate communities of color,” according to New York University law professor Deborah N. Archer (Evans, 2021; Archer, 2020).

Cities such as New York, Miami, Chicago, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, Oakland, Nashville, Baltimore, Atlanta, and Buffalo were all harmed by these highway expansion plans (Dottle et al., 2021). In Buffalo, the home of the nation’s first fully connected citywide park and parkway system, the Buffalo Park System designed by the Father of Landscape Architecture (Frederick Law Olmsted) and Calvert Vaux, originally included three major parks and several picturesque parkways. However, as mentioned previously, Humboldt Parkway was destroyed by the intrusion of the six-lane Expressway. Today, Buffalo’s East Side, where Humboldt Parkway once sat, has a significant green space deficit and the residents “have access to 54% less nearby park space than those living in White neighborhoods”(Supplemental Figure 11) (TPL, 2024). Yet, East Side residents endure the brunt of asthma cases. The asthma prevalence is in the 95-100th percentile compared to everyone else in the United States and Black vs. White Buffalonians experience a 500% higher rate of hospitalization for asthma (Supplemental Figure 3) (Murphy et al., 2022; USEPA, n.d.). Correspondingly, research has shown that living in close proximity to a greener environment during childhood is associated with a lower prevalence of asthma (Hartley et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2023; Cavaleiro et al., 2021).

The Omitted Environmental Impact Statement

Working within the USDOT Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, NYSDOT has proposed the reconstruction of a depressed portion of the Expressway (NYSDOT, 2023b; USDOT, 2023). This project would blast and dig down as much as 20-feet at the northern end, and then completely replace the massive existing reinforced concrete retaining walls to build a $1 billion ¾-mile tunnel. (Supplemental Figure 12 and 13) Construction is currently scheduled to begin in the winter of 2024; however, five lawsuits have been filed calling for a more comprehensive evaluation process that could lead to healthier outcomes for the predominately Black communities adjacent to the Expressway. Article 78 Petitions have been filed by the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU), the Western New York Youth Climate Council (WNYYCC) and the East Side Parkways Coalition (ESP). ESP is a community advocacy organization formed by Candace Moppins and Brad Wales in the summer of 2023. ESP has also teamed-up with We Are Women Warriors (WAWW), led by former Buffalo Common Council Member and Erie County Legislator Betty Jean Grant and local activist Sherry Sherrill to host community information sessions and to canvas hundreds of homeowners in the immediate Humboldt Parkway neighborhoods and on the East Side. The WAWW/ESP canvasing events opened the door to meeting directly affected residents and discussing the potential effects, and the construction schedule of the proposed Tunnel. (Supplemental Figure 14-17) These efforts eventually garnered 61 plaintiffs for the ESP lawsuit, many of whom live very close to the Expressway (Supplemental Figure 18). Petitioners are calling for an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) process rather than the shorter Environmental Assessment (EA) form that has been fast-tracked by NYSDOT. As of this writing, court dates are set for October 2024. Several safeguards, improvements, and alternatives could be explored in an EIS and with a more inclusive public engagement process including, but not limited to, the following list.

1. A Health Impact Assessment (HIA) as defined by the U.S. EPA and with a long-term adverse health effects survey (USEPA, 2024)

2. Community Benefit Agreements (CBA) negotiated before approvals to move forward into construction.

● Considering current conditions in Buffalo, the goal should be that the CBAs for the East Side are as advantageous and protective as possible.

3. Compliance with New York State Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA)

● CLCPA sets thresholds for vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and requires that agencies prioritize emissions reductions and mitigate actions in “disadvantaged” and overburdened communities (NYDEC, 2019a; NYDEC 2019b).

4. An 80-year Economic Development Study of infusing 75,000 cars back through local commercial districts (Meier, n.d.).

5. Complete Expressway removal and the full restoration of Humboldt Parkway

NYCLU’s Petition is critical of the NYSDOT for conducting an EA instead of an EIS in an effort to speed or expediate the process, as recorded in NYSDOT’s Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes from 2009 (NYSDOT, 2009). NYCLU quotes the NYSDOT Region 5 Assistant Design Engineer, Craig S. Mozrall, saying that “NYSDOT has decided to complete an Environmental Assessment (as opposed to an Environmental Impact Statement)” to speed up the process (NYCLU, 2024a). NYCLU’s Petition further asserts that NYSDOT committed a “clear violation of the State Environmental Quality Review Act and Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act” for failing to conduct an EIS and subsequently NYSDOT made a “determination…affected by an error of law” that is “arbitrary and capricious” (NYCLU, 2024a; NYCLU, 2024b). Additionally, at these early meetings with selected community groups, nearly a dozen years prior to the Public Hearings required by law to gather input on potential designs, NYSDOT had already indicated preferred alternatives. The following statements were made supporting pre-determined decisions to maintain the Expressway, and as a consequence, to not fully restore Humboldt Parkway, at the Advisory Committee Meeting held at the Buffalo Museum of Science (NYSDOT, 2009):

“Early on, we stated that we won't look at alternatives that will change the function of the expressway. If we decide now that we are going to consider different functions, we need to do that now. We need to keep focused.”

Darrell Kaminski, NYSDOT Region 5, Regional Design Engineer, September 24, 2009

“Have decided the expressway will remain an expressway – 3 lanes inbound, 3 lanes outbound.”

Craig S. Mozrall, NYSDOT Region 5, Assistant Design Engineer, September 24, 2009

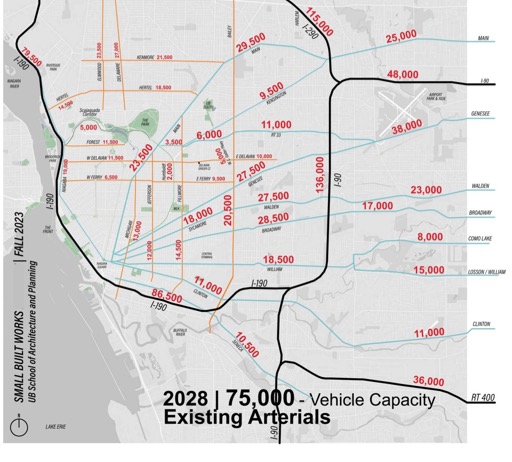

Transportation Infrastructure Evaluation System

Environmental reparation and efforts to “reconnect communities” by redressing the errors of racist urban planning can only truly be addressed if compassionate, inclusive options, such as complete highway removal, are seriously considered when appropriate. Framing these objectives, TIES is presented as a proposed paradigm with five decision-making tiers and suggestions for setting priorities (Table 1). TIES starts from complete highway removal and ends with highway expansion and redesign. It seems clear that maintaining transportation corridors, specifically “maintaining vehicular capacity,” which has been the primary decision-making criteria in Buffalo, cannot be the unilateral default solution for addressing advanced age highways. A comparison of Google Earth aerial renderings illustrates the lack of propriety in the decision-making process when maintaining vehicular capacity is prioritized over historic cultural assets and the health of the adjacent community (Supplemental Figure 19-21). The Expressway is no longer essential based on a redistribution of its average daily traffic (ADT) of 75,000 cars as mapped by UB Small Built Works (Figure B). This figure demonstrates how the radials, such as Main Street, Kensington Avenue, Genesee Street, Walden Avenue /Sycamore Street, William Street, Clinton Street, and Broadway are more than sufficient to handle the current ADT as well as the projected ADT in 2028. To reiterate, “Tier One – Complete Highway Removal” describes what is needed in Buffalo for basic health, as well as environmental, social, and transportation justice.

Figure B.

Kensington Expressway Average Daily Traffic Redistribution Map

Table 1. Transportation Infrastructure Evaluation System (TIES)

|

TIER 1 |

When Complete Highway Removal should be the Preferred Alternative |

|

|

Initial fundamental ascertainment: Did the highway destroy, diminish, or impair a regional asset such as a natural waterway, historic or cultural district, or other culturally significant, or environmentally significant regional asset? For example, in Buffalo, the construction of the Expressway demolished Humboldt Parkway, an Olmstedian treasure of the city. |

||

|

Use Complete Highway Removal |

When the highway is known to cause adverse health effects for the local population, even as per Res ipsa loquitur ● In evaluating highways that have bifurcated populated areas, a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) should be required as a baseline for all DOT highway projects to determine the historic and current extent of the community’s adverse health effects. |

|

|

When the highway is not essential for the efficient transportation needs of the metro region ● The population size of Buffalo no longer requires two expressways coming in from the East and the radials are more than sufficient to maintain the traffic. Furthermore, MIOVISION, a timed-light technology will speed travel times on the radials. |

||

|

When completely removing the highway is the most cost-effective solution, both in direct project costs, and also considering the duration of disruption in adjacent neighborhoods ● For example, in Buffalo, removing the Expressway and fully restoring Humboldt Parkway will cost less because the massive concrete retaining walls would not need to be removed and there would be no blasting. The construction duration will probably be shorter as well, for the same reasons (NYSDOT, 2023b). |

||

|

When the long-term economic benefits to the community overwhelmingly favors putting cars and transit stops back onto original/historic city streets ● For all DOT modifications to urban transportation infrastructure, a thorough evaluation of the potential economic impacts of returning commerce to streets in the city should be required. |

||

|

When maintaining the highway perpetuates environmental racism ● It is well-documented that when the U.S. Interstate Highway System was originally built-out, many urban highways were constructed through communities of color, and these neighborhoods have experienced a substantial decrease in quality of life, including a deterioration of health and blunted social and economic mobility. |

||

|

TIER 2 |

When Highway Removal to a Boulevard should be the Preferred Alternative |

|

|

Initial fundamental ascertainment: Did the highway destroy, diminish, or impair a regional asset such as a natural waterway, historic or cultural district, or other culturally significant, or environmentally significant regional asset? |

||

|

Use Highway Removal to a Boulevard |

When maintaining a reduced volume transportation corridor is essential for the efficient transportation needs of the metro region, with the onus of proof on the transportation authority

● This has been successful in Portland, Milwaukee, Rochester, Boston, Niagara Falls, Montreal, New Haven, and the Bronx, and is planned for Detroit and Syracuse. |

|

|

● When creating a boulevard would not cause adverse health effects for the local population, with the onus of proof on the transportation authority |

||

|

● When creating a boulevard is the most cost-effective solution |

||

|

● When creating a boulevard would not perpetuate environmental racism, with the onus of proof on the transportation authority |

||

|

TIER 3 |

When Highway Redesign to a Cap should be the Preferred Alternative |

|

|

Initial fundamental ascertainment: Did the highway destroy, diminish, or impair a regional asset such as a natural waterway, historic or cultural district, or other culturally significant, or environmentally significant regional asset? |

||

|

Use Highway Redesign to a Cap |

When maintaining the highway transportation corridor is essential for the efficient transportation needs of the metro region, with the onus of proof on the transportation authority

● Considering that we must enforce a global reduction in vehicle miles traveled (VMTs), in-depth studies should also be required to compare possible public transit options against the proposed highway cap. ● An HIA should be required. ● This approach with downtown caps has been successful in non-residential areas, such as Seattle, Boston, and many others. |

|

|

TIER 4 |

When Highway Repair with minor Redesign should be the Preferred Alternative |

|

|

Initial fundamental ascertainment: Did the highway destroy, diminish, or impair a regional asset such as a natural waterway, historic or cultural district, or other culturally significant, or environmentally significant regional asset? |

||

|

Highway Repair with minor Redesign |

When maintaining the highway transportation corridor is essential for the efficient transportation needs of the metro region, with the onus of proof on the transportation authority

● This Tier option essentially maintains the status quo. For many projects, this could be considered the “No Build” option during an environmental review process. |

|

|

TIER 5 |

When Highway Expansion could be the Preferred Alternative |

|

|

Initial fundamental ascertainment: Did the highway destroy, diminish, or impair a regional asset such as a natural waterway, historic or cultural district, or other culturally significant, or environmentally significant regional asset? |

||

|

Use Highway Expansion

|

When redesign calls for expanding the highway transportation corridor, with the onus of proof on the transportation authority

● Considering that we need to enforce a global reduction in VMTs, in-depth studies should also be required to compare possible public transit options against the proposed highway expansion. This Tier option should always be met with a healthy dose of skepticism. ● An HIA should be required. ● Moving forward, in 2024 and beyond, it should become increasingly difficult to secure approvals for highway expansion. |

|

Transportation Infrastructure Evaluation System (TIES) was conceived and written by Brad Wales with Dr. Jennifer D. Roberts.

ESP has begun collaborating with community advocates in the Scajaquada Corridor Coalition (SCC), a group with members who have been working for decades toward the highway removal of the aforementioned Scajaquada Expressway - Route 198 in what is now called the Region Central initiative (GBNRTC, 2024). There is a growing awareness and support in Buffalo for a unified plan. Humboldt Parkway originally included parts of both the Expressway and Route 198; so the two highways will need to be considered together in order to achieve one fully restored Humboldt Parkway. TIES evaluation criteria could be creatively and productively applied to Route 198 as a “Tier Two – Highway Removal to a Boulevard” west of Lincoln Parkway, and a “Tier One – Complete Highway Removal” through the historic Olmsted landscapes east of Lincoln Parkway. Looking optimistically to the future, the current I-190 Expressway cuts off the City from the Lake Erie and Niagara River waterfronts, yet because it is essential for the efficient transportation needs of the metro region, the preferred alternative that would still provide waterfront access would be a Tier Two improvement (Supplemental Figure 22). This would be a tremendously impactful project to address in the not too distant future.

Conclusion

The Interstate and Defense Highway System “fundamentally restructured urban America” and in many cities the results of this restructuring have been devastating (Evans, 2021; Archer, 2020). For Buffalo, in particular, there are numerous multi-generational tragedies, one of which was the destruction of Humboldt Parkway, a 2-mile-long, 188-foot-wide green space bordered by rows of Maple and Elm trees in the 1960s (Supplemental Figure 23-25) (Roberts, 2023). Today’s stories, recounted at ESP meetings and events, are of family members who lived along Humboldt Parkway and near the Expressway that are now suffering from asthma, a myriad of chronic conditions and increased mortality. Moreover, we can clearly see the pervasive decay of the built environments adjacent to the Expressway. There are houses blackened by vehicle exhaust and falling into disrepair, cultural and commercial districts that have been virtually erased, and vacant churches with overlooked historic and architectural significance. Now that the initial construction projects of the Interstate and Defense Highway System are reaching the end of their service life, it is time to re-evaluate the core functionality of the system. If President Eisenhower never intended the highways to go through cities, and these highways are well-documented to have caused so much harm, then why should it be assumed we need to rebuild them? As a nation, with so much government funding on the table, are we going to double-down on the mistakes of the past, or are we going to “right the wrongs of the past”? Ironically, these are the words New York State Governor Kathy Hochul and NYSDOT have used to promote the proposed $1 billion ¾-mile tunnel, which in reality, would cement in-place the Expressway and continue to perpetuate the existing environmental racism (Hochul, 2023; WGRZ, 2024). The climate crisis is happening, but NYSDOT continues to prioritize car-centric transportation infrastructure, one of the largest contributors of greenhouse gasses. Ultimately, this is why we are suggesting TIES as a tool to prioritize health and achieve environmental, social, and transportation justice. TIES is offered for Buffalo’s East Side residents and the countless number of communities throughout the nation that have been marginalized by historic and current day transit injustices. There is still hope because the conclusion to Buffalo’s story has not yet been written. There is still time to speak truth to power in Buffalo and more inclusively “reconnect the community.”

Correspondence should be addressed to

Jennifer D. Roberts

● Jennifer D. Roberts: 0000-0002-1850-4341

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

References

Archer, D. N. (2020). “White Men’s Roads Through Black Men’s Homes”*: Advancing Racial Equity Through Highway Reconstruction. Vanderbilt Law Review, Vol. 73, No 5. [cited 2023 June 30]; Available from: https://cdn.vanderbilt.edu/vu-wp0/wp-content/uploads/sites/278/2020/10/19130728/White-Mens-Roads-Through-Black-Mens-Homes-Advancing-Racial-Equity-Through-Highway-Reconstruction.pdf.

Borchardt, G. M. (2013). Making D.C. Democracy's Capital: Local Activism, the 'Federal State', and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Washington, D.C. University of Notre Dame Dissertation, American Studies. George Washington University. [cited 2024 August 27]; Available from: https://scholarspace.library.gwu.edu/downloads/nz805z886?disposition=inline&locale=en.

Cavaleiro Rufo, J., Paciência, I., Hoffimann, E., Moreira, A., Barros, H. & Ribeiro, A. I. (2021). The neighbourhood natural environment is associated with asthma in children: A birth cohort study. Allergy; 76(1): p. 348-358.

Chen, S. L., Chang, S. W., Chen, Y. J., & Chen, H. L. (2021). Possible warming effect of fine particulate matter in the atmosphere. Communications Earth & Environment; 2(1): p. 208.

Dottle, R., Bliss, L., & Robles, P. (2021). What It Looks Like to Reconnect Black Communities Torn Apart by Highways. Bloomberg. [cited 2024 August 30]; Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-urban-highways-infrastructure-racism/.

Eisenhower, D. D. (1919). Memorandum from Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower to the Chief, Motor Transport Corps, with attached report on the Trans-Continental Trip, November 3, 1919. DDE's Records as President, President's Personal File, Box 967, 1075 Greany Maj. William C.; NAID #1055071. Eisenhower Library. [cited 2024 August 19]; Available from: https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/research/online-documents/1919-convoy/1919-11-03-dde-to-chief.pdf.

Evans, F. (2021). How Interstate Highways Gutted Communities—and Reinforced Segregation. History.com. [cited 2024 August 30]; Available from: https://www.history.com/news/interstate-highway-system-infrastructure-construction-segregation.

GBNRTC. (2024). Region Central Initiative. Greater Buffalo Niagara Regional Transportation Council. [cited 2024 September 2]; Available from: https://www.gbnrtc.org/regioncentral-about.

Hartley, K., Ryan, P., Brokamp, C., & Gillespie, G. L. (2020). Effect of greenness on asthma in children: A systematic review. Public Health Nurs; 37(3): p. 453-460.

Hochul, K. (2023). Governor Hochul Announces City Street Enhancements as Part of Kensington Expressway Project in The City of Buffalo. June 19, 2023. New York State. [cited 2024 August 31]; Available from: https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-hochul-announces-city-street-enhancements-part-kensington-expressway-project-city

Hu, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, S., Tan, J., Yu, G., Yan, C., Yin, Y., Li, S., & Tong, S. (2023). Higher greenspace exposure is associated with a decreased risk of childhood asthma in Shanghai - A megacity in China. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf; 256: p. 114868.

Kowsky, F.R. & Carr, E. (2018). The Best Planned City in the World: Olmsted, Vaux, and the Buffalo Park System. 2018: Library of American Landscape History.

McAndrew, M. (2024). Air quality in Hamlin Park neighborhood - August 14, 2024. Buffalo News. [cited 2024 August 31]; Available from: https://buffalonews.com/news/local/air-quality-in-hamlin-park-neighborhood/html_7dab3150-5a4b-11ef-8a31-eb8c7f982873.html.

Meier, J. D. (n.d.). The New Economy Cycle (80 Years). Sources of Insight. [cited 2024 September 2]; Available from: https://sourcesofinsight.com/the-80-year-new-economy-cycle/.

Murphy, T. F., Robinson, R. H., Wofford, K. M., Lesse, A. J., Grinslade, S., Taylor, H. L., Jr., Pointer, K. M., Nicholas, G. F., & Orom, H. (2022). A community-university run conference as a catalyst for addressing health disparities in an urban community. J Clin Transl Sci; 6(1): p. e67.

NYCLU. (2024a). Gwendolyn Harris and James Ragland v. Marie Therese Dominguez (Commissioner of the New York State Department of Transportation, et al., Supreme Court of the State of New York, County of Erie. New York Civil Liberties Union Racial Justice Center. [cited 2024 September 2]; Available from: https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=https://www.nyclu.org/uploads/2024/06/NYCLU-v-NYSDOT-Petition.pdf.

NYCLU. (2024b). NYCLU Sues NYS Department of Transportation for Refusing to Fully Study and Address Environmental Hazards Caused by Buffalo’s Kensington Expressway Project - June 15, 2024. New York Civil Liberties Union. [cited 2024 September 2]; Available from: https://www.nyclu.org/press-release/nyclu-sues-nys-department-of-transportation-for-refusing-to-fully-study-and-address-environmental-hazards-caused-by-buffalos-kensington-expressway-project

NYDEC. (2019). New York State Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act - Disadvantaged Communities Criteria. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. [cited 2024 September 2]; Available from: https://climate.ny.gov/resources/disadvantaged-communities-criteria/.

NYDEC. (2019). New York State Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. [cited 2024 September 2]; Available from: https://climate.ny.gov.

NYSDEC. (2024). Buffalo, Tonawanda, and Niagara Falls - New York State Community Air Monitoring Initiative. August 12, 2024. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. [cited 2024 August 31]; Available from: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/collections/b39806cbc7ea4b139b79713720dab25f?item=4.

NYSDOT. (2009). Meeting Minutes - PIN 5512.52 NY Route 33, Humboldt Parkway Reconnection. Advisory Committee Meeting #3, September 24, 2009, Buffalo Museum of Science. 2009.

NYSDOT. (2023a). NYSDOT Transportation Project Report – Draft Design Report/Environmental Assessment (DDR/EA - September 12, 2023) NYS Route 33, Kensington Expressway Project – PIN: 5512.52 – City of Buffalo – Erie County; pg 22. . New York State Department of Transportation. [cited 2024 August 31]; Available from: https://kensingtonexpressway.dot.ny.gov/Content/files/DraftDesignReport/Draft%20Design%20Report_Environmental%20Assesment.pdf.

NYSDOT. (2023b). NYS Route 33, Kensington Expressway Project Project Identification Number (PIN): 5512.52. City of Buffalo, Erie County. (September 2023). Draft Design Report/Environmental Assessment, pg 22. New York State Department of Transportation. [cited 2024 August 29]; Available from: https://kensingtonexpressway.dot.ny.gov/Content/files/DraftDesignReport/Draft%20Design%20Report_Environmental%20Assesment.pdf.

NYSDOT. (2024). NYS Route 33, Kensington Expressway Project. Project Identification Number (PIN): 5512.52. City of Buffalo, Erie County. (January 2024). Final Draft Report/Environmental Assessment. New York State Department of Transportation. [cited 2024 August 29]; Available from: https://kensingtonexpressway.dot.ny.gov/Content/files/FinalReport/551252%20Final_DR_EA_2_16_24.pdf.

Park, S., Allen, R. J., & Lim, C. H. (2020). A likely increase in fine particulate matter and premature mortality under future climate change. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health; 13(2): p. 143-151.

Reft, R., de Lucas, A. P., & Retzlaff, R. (2023). Justice and the Interstates: The Racist Truth about Urban Highways. 2023: Island Press.

Roberts, J. D. (2023). From Environmental Racism to Environmental Reparation: The Story of One American City. J Phys Act Health; 20(11): p. 994-997.

Shuman, M. (2024). New map shows areas of Buffalo with worst air pollution - August 15, 2024. Buffalo News. [cited 2024 August 31]; Available from: https://buffalonews.com/news/local/new-map-shows-areas-of-buffalo-with-worst-air-pollution/article_f9f1eed4-5a73-11ef-8966-b7ac001185ae.html.

Simpson, C. G. (2020). The D.C. Black liberation movement seen through the life of Reginald H. Booker. Washington Area Spark. January 28, 2020. [cited 2024 August 27]; Available from: https://washingtonareaspark.com/tag/public-transportation/.

TPL. (2024). 2024 ParkScore Index - Buffalo, NY. Trust for Public Land. [cited 2024 August 30]; Available from: https://parkserve.tpl.org/downloads/pdfs/Buffalo_NY.pdf.

U.S.C. (1956). The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, Public Law 627, Chapter 462. June 29, 1956. 84th United States Congress. [cited 2024 August 19]; Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-70/pdf/STATUTE-70-Pg374.pdf.

USDOT. (2023). Biden-Harris Administration Announces $55.59 million Grant for Kensington Expressway Project in Buffalo, New York as Part of Program to Reconnect Communities. U.S. Department of Transportation. [cited 2024 August 29]; Available from: https://www.transportation.gov/briefing-room/biden-harris-administration-announces-5559-million-grant-kensington-expressway.

USDOT. (2021). Highway Statistics Series - Highway Statistics 2020. U.S. Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration. Policy and Government Affairs, Office of Highway Policy Information. [cited 2024 August 20]; Available from: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2020/hm72.cfm.

USEPA. (n.d.). EJScreen: Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool - Buffalo, NY. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. [cited 2024 August 29]; Available from: https://ejscreen.epa.gov/mapper/.

USEPA. (2024). Health Impact Assessments. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. [cited 2024 September 2]; Available from: https://www.epa.gov/healthresearch/health-impact-assessments#:~:text=HIA%20is%20a%20tool%20designed,before%20the%20decision%20is%20made.

WGRZ. (2024). Kensington Expressway Projects gets green light to move forward to next phase. WGRZ - Channel 2. [cited 2024 August 31]; Available from: https://www.wgrz.com/article/news/local/kensington-expressway-project/71-8f635785-d0f6-46a9-a211-e75565cc190a.

Yoo, E. H. & Roberts, J. E. (2024). Differential effects of air pollution exposure on mental health: Historical redlining in New York State. Sci Total Environ; 948: p. 174516.

[1] NYSDOT reports 75,000 vehicles per day in the Final Design Report/Environmental Assessment (FDR/EA) of January 2024, page 11. Available from: https://kensingtonexpressway.dot.ny.gov/Content/files/FinalReport/551252%20Final_DR_EA_2_16_24.pdf.